The mental health impact of Covid-19

Times of crisis are stressful for almost everyone: whether it is the effect of reading the news, the fear about our own health or the health of loved ones, fear around economic safety and potential or acute unemployment – stressors are manifold. Below are the key areas of direct and indirect mental health impact of Covid-19.

Loss of coherence

First studies1 show the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on our sense of coherence. Coherence can be an important buffer in managing stress and anxiety during the pandemic. This basically comes to say: we need stability to deal with uncertainty and stress.

Quarantine

The negative psychological effects of quarantine itself include post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion and anger, with stress increasing due to longer duration, fear, frustration, boredom, inadequate supplies, inadequate information, financial loss, and stigma.

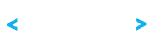

Unemployment

Unemployment has already been identified as a key source for mental illness in independent studies2. Earlier this year, the OECD predicted global unemployment to increase from 5.3 end 2019 to 9.4% at the end of 2020, or 12.6% in case of a second pandemic wave. Millions of people have lost their work during the crisis, with a large number of additional people being affected by the insecurity of their jobs during the crisis and in its aftermath.

External pressure

Perceived or real pressure on performance during the stay-at-home time, whether in the job or in other activities, are increasing the likelihood for individuals to experience stress and burnout. The direct effects of the crisis can be an additional burden, whether through sick or deceased relatives, increased vulnerability, unemployment and lack of finances, or a front-line job.

Healthcare workers & Covid-19 patients

PTSD was the most common psychiatric disorder to arise after the SARS crisis (see examples for healthcare workers in Taiwan and patients in Toronto), and the early outbreak in Wuhan led to similar observations of increased posttraumatic stress symptoms. Recent studies show that nearly 20% of Covid-19 patients develop some form of mental illness three months within testing positive. People with a pre-existing mental health condition were also 65% more likely to contract the virus.

Minorities & vulnerable groups

Unemployment, low income, poverty, debt, poor housing, and other experiences of socioeconomic disadvantage are consistently associated with poorer mental health3. Additionally, these very same conditions also increase the likelihood of contracting Covid-194.

In a statement related to the release of a new report, United Nations Special Rapporteur Dainius Pūras pointed out that “Mental health policies and services are in crisis – not a crisis of chemical imbalances, but of power imbalances”. Interestingly, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (and specifically SDG 3 – Good Health and Wellbeing) do not hold any targets or specific indicators related to Mental Health in particular.

Activists & community organizers

Another area that remains largely undocumented are the mental health effects on activitsts, community organizers and leaders of global movements and causes. While those groups usually have a strong drive to support others, their personal resilience alone might not be sufficient to solely lead through a global pandemic. In conferences like HIV2020, activists have been calling for more attention to the mental health aspects of community work. With community organizers and local volunteers being a key aspect of the Covid-19 response especially in areas where support is otherwise limited, the effects on those groups require attention as well.

Our mental health and productivity is suffering - along with our economy

Mental distress

A major longitudinal study5 among citizens in the UK highlighted the mental health impact of Covid-19. It shows that participants experiencing clinically significant mental distress rose from 18.9 to 27.3% in April 2020, one month into lockdown. The study found comparatively higher scores of mental distress in women, young people, those with school children and those living alone. People who were unemployed, key workers and those living in low-income households also seemed to be disproportionately affected. Taking previous trends into account, the study clearly highlights an increase in mental distress during the crisis.

Low life satisfaction

A study by McKinsey6 shows that average life satisfaction in Europe has reached the lowest level since 1980 this April. It also highlights the proportionally large role that mental health seems to play in citizen’s determinants of overall life satisfaction. This clearly shows that the mental health impact of Covid-19 is an area of necessary attention that cannot be missed in the aftermath of the crisis.

Economic impact and employee productivity

McKinsey quantifies the impact on wellbeing as 3.5 times the size of losses experienced in GDP, and points out further long-term effects. Employee disengagement and productivity loss is a major cost factor for companies as well. A 2017 Gallup study indicates that a disengaged employee costs a company 34% of their salary.

Distanced engagement

Work culture, and a company’s CSR activities, can be potent drivers of engagement – but they are harder to keep up in times of social distancing. A recent study by the Economist and Dropbox shows that one in four respondents see their focus impacted by feeling disconnected from colleagues.

This comes to show the importance of active prevention, early care and strong employee connections not only from the standpoint of care, but from a financial standpoint as well.

The role of technology: Connection in a disconnected world?

It is not only the current effect of the crisis that impacts our health – the technology solutions we use on a daily basis may play a role as well. But despite their often known health implications, during times of social distancing they often stay our only lifeline of connection in a disconnected world. We all heard about and experienced zoom fatigue over the last months, but still sometimes embrace the short moments of connection it can bring.

Social Networks

Especially when it comes to so-called social networks, a negative effect on our mental health is increasingly getting recognized. The latest Netflix hit “The Social Dilemma”, speaks to this act of recognition and a newfound conversation. Teenagers that spend more than 3 hours per day engaged with social media are reporting a higher degree of internalizing problems, which is an aspect of increased mental health risk. While this does not per se indicate that social networks, or technology solutions, are the cause of increased mental health risk, it leads to an important question: How can we build solutions that are actively contributing to building real world social connections, instead of increasing perceived or real isolation and loneliness?

Taking action: Information, prevention and long-term care

Early on, governments, national public health organisations like the CDC as well as the World Health Organisation have shared information and guidance on the mental health impact of Covid-19.

Meditation apps provide free limited services addressing the Covid-19 crisis, and independent therapy apps like TalkSpace provide on-demand therapeutic assistance for a yearly subscription fee. However, while providers see an increase in demand, the focus on this aspect of the crisis is still rather limited.

A need for long-term care

What will probably be one of the key indicators of the long-term mental health impact of Covid-19, along with its impact on economies and healthcare systems, is how well we are able to manage the increased demand for psychological assistance of healthcare workers, communities disproportionately affected by the crisis, those who lost relatives and family members, and those who see a long-term effect of prolonged quarantine, unemployment, or their own Covid-19 diagnosis.

Better prevention

Apart from direct professional assistance and mental health treatment, there is also ample opportunity in preventive mechanisms – solutions that address key influencing factors for mental health. This includes solutions supporting people, and especially vulnerable groups, through the difficulties of unemployment and reskilling, solutions that foster and facilitate close connections and exchange, and solutions that bring more coherence into people’s lives during the time of crisis.

Overall, given the large scope of its impact, interrelations and adverse effects, mental health is likely to emerge as a key priority area for further innovation.

Can technology solutions be beneficial to mental health?

As an innovation studio focused on technology innovation for impact, the key question we are asking ourselves is this: Which, if any, role can technology play in mitigating the mental health impact of Covid-19? How can we improve and lower the impact that unhealthy technology-induced habits have on our mental health?

Solutions that support healthcare and treatment

Digital scheduling and virtual appointments have become increasingly common over the course of this year. This holds especially for psychological treatment without necessary physical exams. Chatbots and virtual assistants are increasingly used to check in with patients and identify crisis situations. Smart textiles and wristbands bring more tactical solutions for stress reduction and biofeedback , while AR/VR can be used to enhance therapy sessions. Overall, it is important to keep in mind that digital solutions can only ever be a supplement to in-person care.

Solutions that improve focus and limit distractions

28% of work time is lost to distractions. The struggle with information overload and false information has been real during this pandemic, increasing our feelings of uncertainty. At the same time, working at a distance makes us more adept to frequently check chats, notifications and incoming messages.

What helps? Solutions that limit distractions and overall screen time, and help us focus on important tasks.

Forest is a great example of such an app – it encourages focused work, while at the same time planting trees based on the progress of users.

Forest is a great example of such an app – it encourages focused work, while at the same time planting trees based on the progress of users.

Freedom blocks distractions across devices.

Solutions that build healthy habits

Habits and routines are extremely important for our sense of coherence. Digital apps and platforms are known for creating habits and app engagement, although this engagement is often not the healthy routine we seek. Can we use the same mechanisms to build habits that improve mental health?

Headspace and Calm are great examples of apps that help to build mindfulness and meditation habits, while Smiling Minds is a free/ non-profit alternative. Habitica focuses on general habit building with the help of gamification, while Fabulous builds habits through behavioural science insights.

Solutions that motivate meaningful connection and exchange

Digital tools form an important aspect of staying connected in times of social isolation. But for our personal wellbeing, it is crucial that we build connections beyond likes and retweets.

Learning, teaching, and volunteering are some great examples of meaningful connection and exchange. They have a positive effect on our wellbeing and satisfaction. In companies, employee volunteering is a great driver for engagement.

Our very own Tiramisu connects people (and employees) to exchange support and contribute to volunteer causes in their area.

Our very own Tiramisu connects people (and employees) to exchange support and contribute to volunteer causes in their area.

Business Model optimization for mental health

Most end user-focused applications and platforms have been developed for one key objective: to increase the screen time of users. This way, they see more ads, spend more money, have more interactions – and improve the bottom line of the producers. Much time and money has been invested in developing advanced mechanisms for keeping users engaged and connected.

For companies and entrepreneurs, it is high time to revisit the business models behind platform, app and network solutions, and put the focus on those models that benefit both users and customers: combining respectful and healthy user engagements with profit opportunities – and positive impact.

Read more insights on technology implications of the Covid-19 crisis in our in-depth report on the topic.

1 Dymecka, Joanna & Gerymski, Rafał & Machnik-Czerwik, Anna. (2020). How does stress affect our life satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic? Moderated mediation analysis of sense of coherence and fear of coronavirus. 10.31234/osf.io/3zjrx.

2 Klaus Moser, Karsten I. Paul (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, June 2009

3 Anna Macintyre, Daniel Ferris, Briana Gonçalves & Neil Quinn (2018). What has economics got to do with it? The impact of socioeconomic factors on mental health and the case for collective action. Palgrave Communications. DOI: 10.1057/s41599-018-0063-2

4 Patel, J. A., Nielsen, F., Badiani, A. A., Assi, S., Unadkat, V. A., Patel, B., Ravindrane, R., & Wardle, H. (2020). Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable. Public health, 183, 110–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.006

5 Sally McManus, Kathryn M Abel et al. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, July 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

6 Tera Allas, David Chinn, Pal Erik Sjatil, and Whitney Zimmerman (2020). Well-being in Europe: Addressing the high cost of COVID-19 on life satisfaction

7 Towers Perrin (2008). Global Workforce Study 2007- 2008. Towers Perrin

8 Riehm KE, Feder KA, Tormohlen KN, et al. Associations Between Time Spent Using Social Media and Internalizing and Externalizing Problems Among US Youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(12):1266–1273. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2325

Maike Gericke

Maike Gericke is an experienced designer, strategist, innovator and marketer. Her passion for emerging technologies and social / environmental impact led her to start the innovation studio Scrypt with Khalid. Together, they rethink, research, build and teach the use of new technologies for impact.